Help yourself, and them, by learning techniques to manage stress in a healthy way.

Brigit Katz, Child Mind Institute

On a recent afternoon, JD Bailey was trying to get her two young daughters to their dance class. A work assignment delayed her attempts to leave the house, and when Bailey was finally ready to go, she realized that her girls still didn’t have their dance clothes on.

She began to feel overwhelmed and frustrated, and in the car ride on the way to the class, she shouted at her daughters for not being ready on time. “Suddenly I was like, ‘What am I doing?’” she recalls, filled with anxiety. “‘This isn’t their fault. This is me.’ ”

Taking cues from you

Witnessing a parent in a state of anxiety can be more than just momentarily unsettling for children. Kids look to their parents for information about how to interpret ambiguous situations; if a parent seems consistently anxious and fearful, the child will determine that a variety of scenarios are unsafe. And there is evidence that children of anxious parents are more likely to exhibit anxiety themselves, a probable combination of genetic risk factors and learned behaviors.

It can be painful to think that, despite your best intentions, you may find yourself transmitting your own stress to your child. But if you are dealing with anxiety and start to notice your child exhibiting anxious behaviors, the first important thing is not to get bogged down by guilt.

your own stress to your child. But if you are dealing with anxiety and start to notice your child exhibiting anxious behaviors, the first important thing is not to get bogged down by guilt.

“There’s no need to punish yourself,” says Dr. Jamie Howard, director of the Stress and Resilience Program at the Child Mind Institute. “It feels really bad to have anxiety, and it’s not easy to turn off.”

But the transmission of anxiety from parent to child is not inevitable. The second important thing to do is implement strategies to help ensure that you do not pass your anxiety on to your kids. That means managing your own stress as effectively as possible, and helping your kids manage theirs. “If a child is prone to anxiety,” Dr. Howard adds, “it’s helpful to know it sooner and to learn the strategies to manage sooner.”

Learn stress management techniques

It can be very difficult to communicate a sense of calm to your child when you are struggling to cope with your own anxiety. A mental health professional can help you work through methods of stress management that will suit your specific needs. As you learn to tolerate stress, you will in turn be teaching your child—who takes cues from your behavior—how to cope with situations of uncertainty or doubt.

It can be very difficult to communicate a sense of calm to your child when you are struggling to cope with your own anxiety. A mental health professional can help you work through methods of stress management that will suit your specific needs. As you learn to tolerate stress, you will in turn be teaching your child—who takes cues from your behavior—how to cope with situations of uncertainty or doubt.

“A big part of treatment for children with anxiety,” explains Dr. Laura Kirmayer, a clinical psychologist, “is actually teaching parents stress tolerance. It’s a simultaneous process—it’s both directing the parent’s anxiety, and then how they also support and scaffold the child’s development of stress tolerance.”

Model stress tolerance

You might find yourself learning strategies in therapy that you can then impart to your child when she is feeling anxious. If, for example, you are working on thinking rationally during times of stress, you can practice those same skills with your child. Say to her: “I understand that you are scared, but what are the chances something scary is actually going to happen?”

Try to maintain a calm, neutral demeanor in front of your child, even as you are working on managing your anxiety.

Dr. Howard says, “Be aware of your facial expressions, the  words you choose, and the intensity of the emotion you express, because kids are reading you. They’re little sponges and they pick up on everything.”

words you choose, and the intensity of the emotion you express, because kids are reading you. They’re little sponges and they pick up on everything.”

Explain your anxiety

While you don’t want your child to witness every anxious moment you experience, you do not have to constantly suppress your emotions. It’s okay—and even healthy—for children to see their parents cope with stress every now and then, but you want to explain why you reacted in the way that you did.

Let’s say, for example, you lost your temper because you were worried about getting your child to school on time. Later, when things are calm, say to her: “Do you remember when I got really frustrated in the morning? I was feeling anxious because you were late for school, and the way I managed my anxiety was by yelling. But there are other ways you can manage it too. Maybe we can come up with a better way of leaving the house each morning.”

Talking about anxiety in this way gives children permission to feel stress, explains Dr. Kirmayer, and sends the message that stress is manageable. “If we feel like we have to constantly protect our children from seeing us sad, or angry, or anxious, we’re subtly giving our children the message that they don’t have permission to feel those feelings, or express them, or manage them,” she adds. “Then we’re also, in a way, giving them an indication that there isn’t a way to manage them when they happen.”

Make a plan

Come up with strategies in advance for managing specific situations that trigger your stress. You may even involve your child in the plan.

If, for example, you find yourself feeling anxious about getting your son ready for bed by a reasonable hour, talk to him about how you can work together to better handle this stressful transition in the future.

Maybe you can come up with a plan wherein he earns points toward a privilege whenever he goes through his evening routine without protesting his bedtime.

These strategies should be used sparingly: You don’t want to put the responsibility on your child to manage your anxiety if it permeates many aspects of your life. But seeing you implement a plan to curb specific anxious moments lets him know that stress can be tolerated and managed.

Know when to disengage

If you know that a situation causes you undue stress, you might want to plan ahead to absent yourself from that situation so your children will not interpret it as unsafe. Let’s say, for example, that school drop-offs fill you with separation anxiety. Eventually you want to be able to take your child to school, but if you are still in treatment, you can ask a co-parent or co-adult to handle the drop off. “

You don’t want to model this very worried, concerned expression upon separating from your children,” says Dr. Howard. “You don’t want them to think that there’s anything dangerous about dropping them off at school.”

In general, if you feel yourself becoming overwhelmed with anxiety in the presence of your child, try to take a break. Danielle Veith, a stay-at-home mom who blogs about her struggles with anxiety, will take some time to herself and engage in stress-relieving activities when she starts to feel acutely anxious. “I have a list of to-do-right-this-second tips for dealing with a panic, which I carry with me: take a walk, drink tea, take a bath, or just get out the door into the air,” she says. “For me, it’s about trusting in the fact that the anxiety will pass and just getting through until it passes.”

Find a support system

Trying to parent while struggling with your own mental health can be a challenge, but you don’t have to do it alone. Rely on the people in your life who will step in when you feel overwhelmed, or even just offer words of support. Those people can be therapists, co-parents, or friends.

Trying to parent while struggling with your own mental health can be a challenge, but you don’t have to do it alone. Rely on the people in your life who will step in when you feel overwhelmed, or even just offer words of support. Those people can be therapists, co-parents, or friends.

“I am a part of an actual support group, but I also have a network of friends,” says Veith. “I am open with friends about who I am, because I need to be able to call on them and ask for help. ”

Information provided by https://childmind.org/article/how-to-avoid-passing-anxiety-on-to-your-kids/

your own stress to your child. But if you are dealing with anxiety and start to notice your child exhibiting anxious behaviors, the first important thing is not to get bogged down by guilt.

your own stress to your child. But if you are dealing with anxiety and start to notice your child exhibiting anxious behaviors, the first important thing is not to get bogged down by guilt. It can be very difficult to communicate a sense of calm to your child when you are struggling to cope with your own anxiety. A mental health professional can help you work through methods of stress management that will suit your specific needs. As you learn to tolerate stress, you will in turn be teaching your child—who takes cues from your behavior—how to cope with situations of uncertainty or doubt.

It can be very difficult to communicate a sense of calm to your child when you are struggling to cope with your own anxiety. A mental health professional can help you work through methods of stress management that will suit your specific needs. As you learn to tolerate stress, you will in turn be teaching your child—who takes cues from your behavior—how to cope with situations of uncertainty or doubt. words you choose, and the intensity of the emotion you express, because kids are reading you. They’re little sponges and they pick up on everything.”

words you choose, and the intensity of the emotion you express, because kids are reading you. They’re little sponges and they pick up on everything.”

Trying to parent while struggling with your own mental health can be a challenge, but you don’t have to do it alone. Rely on the people in your life who will step in when you feel overwhelmed, or even just offer words of support. Those people can be therapists, co-parents, or friends.

Trying to parent while struggling with your own mental health can be a challenge, but you don’t have to do it alone. Rely on the people in your life who will step in when you feel overwhelmed, or even just offer words of support. Those people can be therapists, co-parents, or friends.

Check with your pediatrician

Check with your pediatrician Techniques for calming down

Techniques for calming down As public conversations around coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increase, children may worry about themselves, their family, and friends getting ill with COVID-19. Parents, family members, school staff, and other trusted adults can play an important role in helping children make sense of what they hear in a way that is honest, accurate, and minimizes anxiety or fear.

As public conversations around coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increase, children may worry about themselves, their family, and friends getting ill with COVID-19. Parents, family members, school staff, and other trusted adults can play an important role in helping children make sense of what they hear in a way that is honest, accurate, and minimizes anxiety or fear.

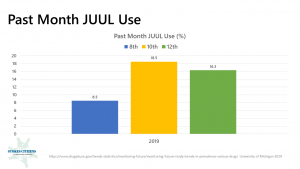

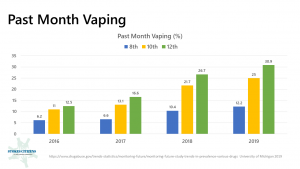

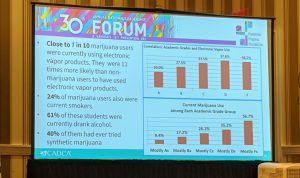

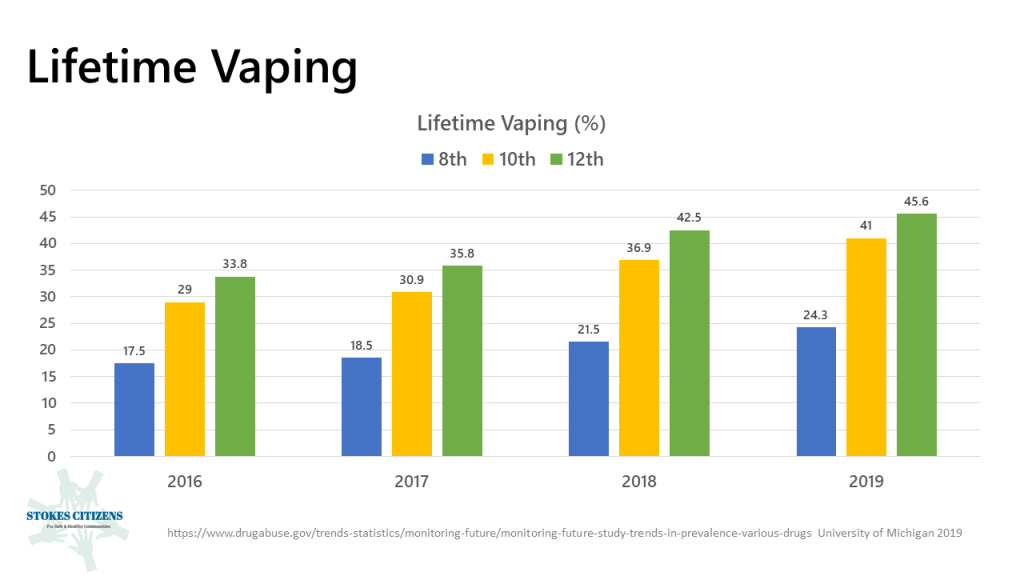

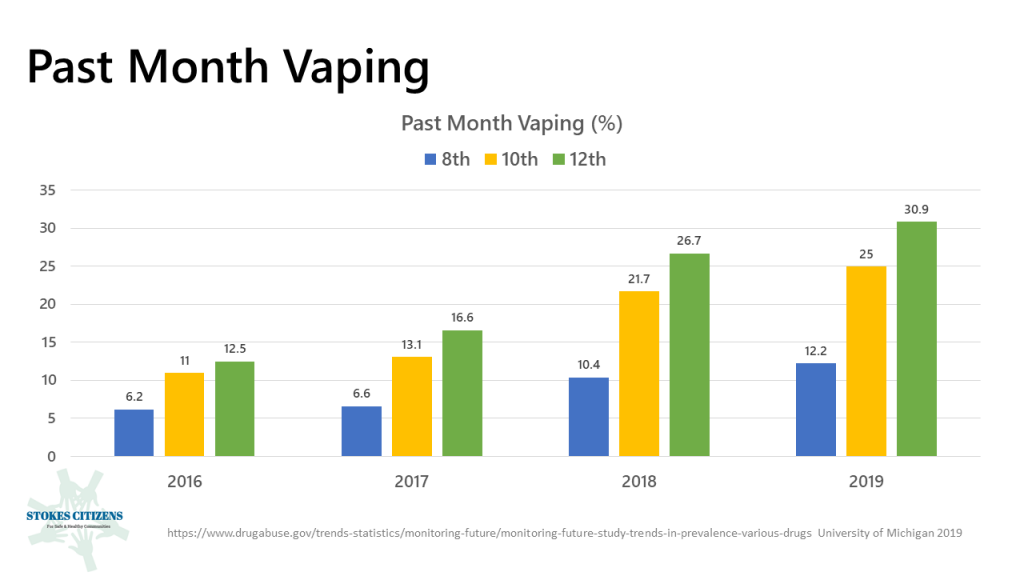

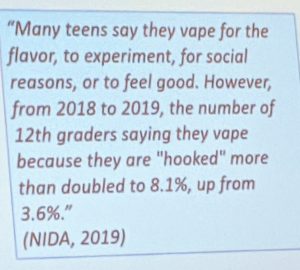

National data suggests that youth past 30-day use of nicotine delivered via vaping devices roughly doubled from 2017 to 2018. This session provided an overview of the strategies in which DFC grant recipients are engaging around vaping prevention, including collecting data on attitudes and use, engaging youth, and building capacity within the community to shed light on this new trend. During this session there an opportunity for participants to share ideas on how to address vaping in their local communities and to discuss emerging findings on the impacts of vaping on youth.

National data suggests that youth past 30-day use of nicotine delivered via vaping devices roughly doubled from 2017 to 2018. This session provided an overview of the strategies in which DFC grant recipients are engaging around vaping prevention, including collecting data on attitudes and use, engaging youth, and building capacity within the community to shed light on this new trend. During this session there an opportunity for participants to share ideas on how to address vaping in their local communities and to discuss emerging findings on the impacts of vaping on youth.