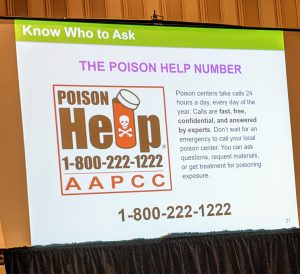

October is National Medicine Abuse Awareness Month

October is National Medicine Abuse Awareness Month

Parents: did you know that 1 in 30 youth ages 12 through 17 has misused cough medicine to get high from its dextromethorphan ingredient?

Over-the-counter cough medicine can have negative outcomes if misused. Securely store and monitor cough medicine in the home to prevent misuse.

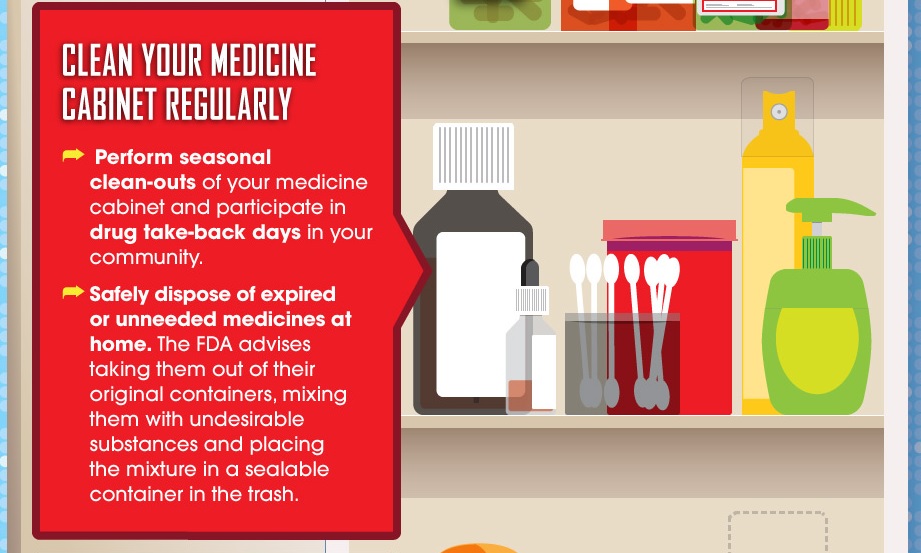

We encourage parents, guardians and caregivers of youth to secure and monitor both prescription and over-the-counter medications.

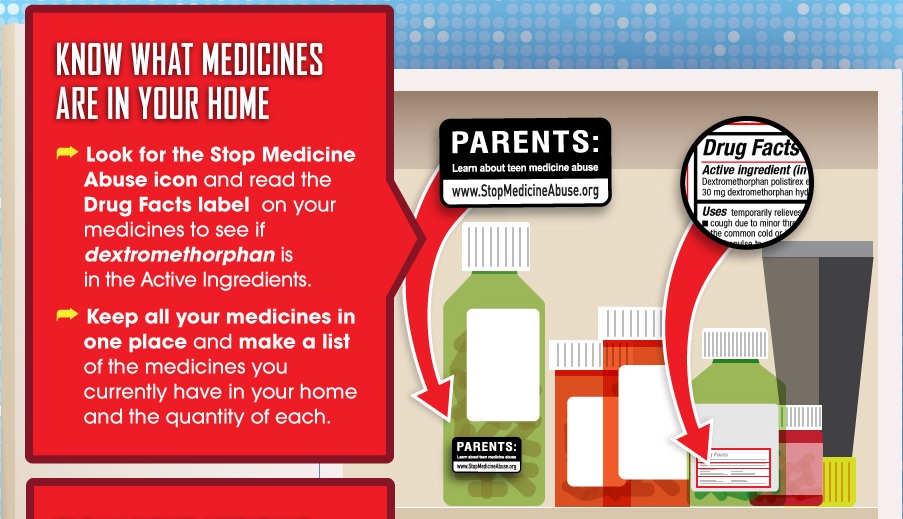

Parents/guardians are encouraged to review the labels on medications in their medicine cabinets

http://www.stopmedicineabuse.org

Make sure you are doing your part to keep your community safe by securing all medications in the home and disposing of medications properly.

We encourage parents and guardians to know the slang terms that are used to describe cough syrup misuse

Pet owners: did you know that the medication the veterinarian prescribed for your pet can be misused by people trying to get high?

Make sure that all medications, for both humans and animals, are securely stored out of sight and out of reach.

Supporting Parents: When Your Child Has Anxious Stomach Aches and Headaches

All kids get an occasional headache or stomach ache — think not enough sleep or too much Halloween candy. But when children get them often, they may be signs of anxiety.

All kids get an occasional headache or stomach ache — think not enough sleep or too much Halloween candy. But when children get them often, they may be signs of anxiety.

Stomach aches in the morning before school. Headaches when there’s a math test on the schedule. Butterflies before a birthday party. Throwing up before a soccer game. These physical symptoms may be the first evidence a parent has that a child is anxious. In fact, the child may not even know she is anxious.

“Especially with kids who may not be able to verbalize what they’re feeling anxious about, the way their anxiety manifests can be through physical symptoms,” explains Amanda Greenspan, LCSW, a clinical social worker at the Child Mind Institute.

Physical symptoms of anxiety

In fact anxiety is associated with a host of physical symptoms, including headaches, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, along with a racing heart, shakiness or sweating — symptoms older people experience when they’re having a panic attack.

All these physical symptoms are related to the fight-or-flight response triggered when the brain detects danger. All of them have a purpose, notes Janine Domingues, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. When she talks to kids about anxious headaches or stomach aches, she explains the role of each.

For instance, she says, “your stomach hurts because your digestive system is shutting down to send blood to other areas of your body. You don’t want to be digesting food at that moment because you’re trying to either flee danger or fight danger.”

Dr. Domingues assures children that these symptoms are not harmful — they’re just their emergency system responding to a false alarm. But it’s important to understand that kids aren’t necessarily inventing their symptoms, and the danger may feel very real to them. Don’t assume a child who spends a lot of time in the nurse’s office at school is doing it intentionally to get out of class. Her acute anxiety may be causing her pain.

“Headaches and stomach aches related to anxiety are still real feelings, and we want to take them seriously,” says Ms. Greenspan.

Check with your pediatrician

Check with your pediatrician

When a child develops a pattern of physical symptoms before school, or other potentially stressful moments, experts recommend that you visit your doctor to rule out medical concerns. But if the child gets a clean bill of health, the next step is to help the child make the connection between their worries and their physical symptoms.

“We help them understand in a very child-friendly way that sometimes our body can actually give us clues into what we’re feeling,” explains Ms. Greenspan.

Parents can start by validating their child’s experience and reframing it in a more helpful way. Instead of telling kids there’s nothing wrong with them, the goal is to tell them that what they’re feeling is worry.

“We give it a name,” adds Dr. Domingues. “We help them connect it to an emotion and label it.”

And after some practice kids are able to identify it, she adds. ” ‘Yes, my stomach hurts and, oh yeah, I remember that’s because I’m feeling worried.’ And after learning some skills to help them calm down, I think they feel a sense of control. And that helps.”

What can parents do to help?

The first thing our experts suggest is something parents should not do, or at least try not to do: Let kids avoid things they are afraid of. It can be very tempting when children are complaining of a headache or stomach ache to let them stay home from school, or skip the party or the game they’re worried about. But avoidance actually reinforces the anxiety.

“If we’re allowing them to avoid it,” says Ms. Greenspan, “then they’re not able to learn that they can tolerate it.” The message needs to be:

“I know it hurts, I know it’s uncomfortable, but I know you can do it.”

Another things parents should not do is ask children leading questions like “Are you worried about the math test?” Questions should be open ended, to avoid suggesting that you expect them to be anxious: “How are you feeling about the math test?”

If the problems your child is having are disrupting his ability to go to school consistently — or concentrate at school, participate in activities, socialize with peers — he might have developed an anxiety disorder that should be treated by a mental health professional. The treatment favored by most clinicians for anxiety disorders is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT helps kids — as young as 5 years old — identify their anxiety and learn skills to reduce it.

The techniques clinicians teach children to calm down body and mind can also be deployed by parents, for children with less impairing symptoms.

Techniques for calming down

Techniques for calming down

Here are some of the techniques clinicians teach anxious children, adapted from CBT and mindfulness training:

-

- Deep breathing: Drawing in air by expanding the belly, sometimes called belly breathing, helps kids relax by slowing breathing, and reducing the heart rate, blood pressure and stress hormones. It can also help relax tense stomach muscles.

- Mindfulness exercises: Techniques such as focusing on what’s around them, what they see and hear, can help pull children away from the anxiety and ground them in the moment.

- Coping statements: Children are taught to “talk back to their worries,” Ms. Greenspan explains. “They can say, ‘I’m feeling scared and I can handle it.’ Or something along the lines of, ‘I’m bigger than my anxiety.’”

- Coping ahead: Children are taught that when you have to do something that makes you nervous, it helps to anticipate that you might have some discomfort, and plan what you can do to counteract it, knowing that if you can push through it, it will get easier.

- Acceptance: This involves acknowledging the discomfort without fighting it. “Instead of trying to push the feeling away and get rid of it,” Dr. Domingues explains, “we ask you to hold onto it and tolerate it and get through it.”

The parents’ role is key

The parents’ role is key

It’s only natural that parents don’t want to see their kids in distress or make them go to school when they’re worried that they’ll throw up. That puts parents in a difficult spot. “What we hear from parents is, ‘We just let him stay home one day — and one day led to three months,’ ” says Dr. Domingues. It’s a slippery slope — the child may ask to stay home more and more.

“So we work with parents a lot around how to find that balance between enabling anxiety and meeting a child where they are,” she adds. “And we also give them statements that they can use to be empathic and encouraging at the same time. For instance: ‘I know that this is really hard and you feel like you’re sick. But we also know that this is anxiety, and you can get through it.’ ”

Sometimes setting up a reward system can help by giving a lot of positive reinforcement for kids pushing through their anxiety.

Parents also face the challenge of tolerating their own anxiety about pushing a child who says she is ill or worried about vomiting. “If your kid is in distress and talking about not wanting to go to school or feeling sick or thinking they might throw up,” says Dr. Domingues, “then you’re, as a parent, also anxious that that might happen.”

Information provided by https://childmind.org/article/anxious-stomach-aches-and-headaches/

Tip for Parents/Guardians on How to Support Kids in the Home During Coronavirus

As schools close and workplaces go remote to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus, parents everywhere are struggling to keep children healthy and occupied.

If you’re anxious about how to protect and nurture kids through this crisis — often juggling work obligations at the same time — you’re in good (virtual) company.

KEEP ROUTINES IN PLACE

KEEP ROUTINES IN PLACE

- The experts all agree that setting and sticking to a regular schedule is key, even when you’re all at home all day. Kids should get up, eat and go to bed at their normal times. Consistency and structure are calming during times of stress. Kids, especially younger ones or those who are anxious, benefit from knowing what’s going to happen and when.

- The schedule can mimic a school or day camp schedule, changing activities at predictable intervals, and alternating periods of study and play.

- It may help to print out a schedule and go over it as a family each morning. Setting a timer will help kids know when activities are about to begin or end. Having regular reminders will help head off meltdowns when it’s time to transition from one thing to the next.

BE CREATIVE ABOUT NEW ACTIVITIES AND EXERCISE

- Incorporate new activities into your routine, like doing a puzzle or having family game time in the evening. For example, my family is baking our way through a favorite dessert cookbook together with my daughter as sous chef.

- Build in activities that help everyone get some exercise (without contact with other kids or things touched by other kids, like playground equipment). Take a daily family walk or bike ride or do yoga — great ways to let kids burn off energy and make sure everyone is staying active.

- David Anderson, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute, recommends brainstorming ways to go “back to the 80s,” before the time of screen prevalence. “I’ve been asking parents to think about their favorite activities at summer camp or at home before screens,” he says. “They often then generate lists of arts and crafts activities, science projects, imaginary games, musical activities, board games, household projects, etc.”

MANAGE YOUR OWN ANXIETY

- It’s completely understandable to be anxious right now (how could we not be?) but how we manage that anxiety has a big impact on our kids. Keeping your worries in check will help your whole family navigate this uncertain situation as easily as possible.

- “Watch out for catastrophic thinking,” says Mark Reinecke, PhD, a clinical psychologist with the Child Mind Institute. For example, assuming every cough is a sign you’ve been infected, or reading news stories that dwell on worst-case scenarios. “Keep a sense of perspective, engage in solution-focused thinking and balance this with mindful acceptance.”

- For those moments when you do catch yourself feeling anxious, try to avoid talking about your concerns within earshot of children. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, step away and take a break. That could look like taking a shower or going outside or into another room and taking a few deep breaths.

LIMIT CONSUMPTION OF NEWS

- Staying informed is important, but it’s a good idea to limit consumption of news and social media that has the potential to feed your anxiety, and that of your kids. Turn the TV off and mute or unfollow friends or co-workers who are prone to sharing panic-inducing posts.

- Take a social media hiatus or make a point of following accounts that share content that take your mind off the crisis, whether it’s about nature, art, baking or crafts.

STAY IN TOUCH VIRTUALLY

- Keep your support network strong, even when you’re only able to call or text friends and family. Socializing plays an important role in regulating your mood and helping you stay grounded. And the same is true for your children.

- Let kids use social media (within reason) and Skype or FaceTime to stay connected to peers even if they aren’t usually allowed to do so. Communication can help kids feel less alone and mitigate some of the stress that comes from being away from friends.

- Technology can also help younger kids feel closer to relatives or friends they can’t see at the moment. My parents video chat with their granddaughter every night and read her a (digital) bedtime story. It’s not perfect, but it helps us all feel closer and less stressed.

KEEP IT POSITIVE

KEEP IT POSITIVE

- Though adults are feeling apprehensive, to most children the words “School’s closed” are cause for celebration. “My kid was thrilled when he found out school would be closing,” says Rachel Busman, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. Parents, she says, should validate that feeling of excitement and use it as a springboard to help kids stay calm and happy.

- Let kids know that you’re glad they’re excited, but make sure they understand that though it may feel like vacations they’ve had in the past, things will be different this time. For example, Dr. Busman suggests, “It’s so cool to have everyone home together. We’re going to have good time! Remember, though, we’ll still be doing work and sticking to a regular schedule.”

Information provided by https://childmind.org/article/supporting-kids-during-the-covid-19-crisis/

Caring for Someone at Home: COVID-19

Most people who get sick with COVID-19 will have only mild illness and should recover at home.  Care at home can help stop the spread of COVID-19 and help protect people who are at risk for getting seriously ill from COVID-19.

Care at home can help stop the spread of COVID-19 and help protect people who are at risk for getting seriously ill from COVID-19.

Older adults and people of any age with certain serious underlying medical conditions like lung disease, heart disease, or diabetes are AT HIGHER RISK for developing more serious complications from COVID-19 illness and should seek care as soon as symptoms start.

COVID-19 spreads between people who are in close contact (within about 6 feet) through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

Monitor the person for worsening symptoms. Know the emergency warning signs.

-

- Have their healthcare provider’s contact information on hand.

- If they are getting sicker, call their healthcare provider. For medical emergencies, call 911 and notify the dispatch personnel that they have or are suspected to have COVID-19.

Prevent the spread of germs when caring for someone who is sick

-

- Have the person stay in one room, away from other people, including yourself, as much as possible.

- If possible, have them use a separate bathroom.

- Avoid sharing personal household items, like dishes, towels, and bedding

- If facemasks are available, have them wear a facemask when they are around people, including you.

- It the sick person can’t wear a facemask, you should wear one while in the same room with them, if facemasks are available.

- If the sick person needs to be around others (within the home, in a vehicle, or doctor’s office), they should wear a facemask.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after interacting with the sick person. If soap and water are not readily available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Cover all surfaces of your hands and rub them together until they feel dry.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Every day, clean all surfaces that are touched often, like counters, tabletops, and doorknobs

- Use household cleaning sprays or wipes according to the label instructions.

- Wash laundry thoroughly.

- If laundry is soiled, wear disposable gloves and keep the soiled items away from your body while laundering. Wash your hands immediately after removing gloves.

- Avoid having any unnecessary visitors.

- For any additional questions about their care, contact their healthcare provider or state or local health department.

- Have the person stay in one room, away from other people, including yourself, as much as possible.

Stokes County Health Department contact information can be found here.

Information provided by CDC here https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/care-for-someone.html

Managing Anxiety and Stress

Stress and Coping

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may be stressful for people. Fear and anxiety about a disease can be overwhelming and cause strong emotions in adults and children. Coping with stress will make you, the people you care about, and your community stronger.

Everyone reacts differently to stressful situations. How you respond to the outbreak can depend on your background, the things that make you different from other people, and the community you live in.

People who may respond more strongly to the stress of a crisis include

-

-

- Older people and people with chronic diseases who are at higher risk for COVID-19

- Children and teens

- People who are helping with the response to COVID-19, like doctors and other health care providers, or first responders

- People who have mental health conditions including problems with substance use

-

Stress during an infectious disease outbreak can include

-

-

- Fear and worry about your own health and the health of your loved ones

- Changes in sleep or eating patterns

- Difficulty sleeping or concentrating

- Worsening of chronic health problems

- Increased use of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs

-

Taking care of yourself, your friends, and your family can help you cope with stress. Helping others cope with their stress can also make your community stronger.

Things you can do to support yourself

-

- Take breaks from watching, reading, or listening to news stories, including social media. Hearing about the pandemic repeatedly can be upsetting.

- Take care of your body. Take deep breaths, stretch, or meditate. Try to eat healthy, well-balanced meals, exercise regularly, get plenty of sleep, and avoid alcohol and drugs.

- Make time to unwind. Try to do some other activities you enjoy.

- Connect with others. Talk with people you trust about your concerns and how you are feeling.

Information provided by https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prepare/managing-stress-anxiety.html

Talking with children about Coronavirus Disease 2019: Messages for parents, school staff, and others working with children

As public conversations around coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increase, children may worry about themselves, their family, and friends getting ill with COVID-19. Parents, family members, school staff, and other trusted adults can play an important role in helping children make sense of what they hear in a way that is honest, accurate, and minimizes anxiety or fear.

As public conversations around coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) increase, children may worry about themselves, their family, and friends getting ill with COVID-19. Parents, family members, school staff, and other trusted adults can play an important role in helping children make sense of what they hear in a way that is honest, accurate, and minimizes anxiety or fear.

CDC has created guidance to help adults have conversations with children about COVID-19 and ways they can avoid getting and spreading the disease.

general principles for talking to children

Remain calm and reassuring.

-

- Remember that children will react to both what you say and how you say it. They will pick up cues from the conversations you have with them and with others.

Make yourself available to listen and to talk.

-

- Make time to talk. Be sure children know they can come to you when they have questions.

Avoid language that might blame others and lead to stigma.

-

- Remember that viruses can make anyone sick, regardless of a person’s race or ethnicity. Avoid making assumptions about who might have COVID-19.

Pay attention to what children see or hear on television, radio, or online.

-

- Consider reducing the amount of screen time focused on COVID-19. Too much information on one topic can lead to anxiety.

Provide information that is honest and accurate.

-

- Give children information that is truthful and appropriate for the age and developmental level of the child.

- Talk to children about how some stories on COVID-19 on the Internet and social media may be based on rumors and inaccurate information.

Teach children everyday actions to reduce the spread of germs.

-

- Remind children to stay away from people who are coughing or sneezing or sick.

- Remind them to cough or sneeze into a tissue or their elbow, then throw the tissue into the trash.

- Discuss any new actions that may be taken at school to help protect children and school staff.

(e.g., increased handwashing, cancellation of events or activities) - Get children into a handwashing habit.

- Teach them to wash their hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after blowing their nose, coughing, or sneezing; going to the bathroom; and before eating or preparing food.

- If soap and water are not available, teach them to use hand sanitizer. Hand sanitizer should contain at least 60% alcohol. Supervise young children when they use hand sanitizer to prevent swallowing alcohol, especially in schools and childcare facilities.

Facts about COVID-19 for discussions with children

Try to keep information simple and remind them that health and school officials are working hard to keep everyone safe and healthy.

What is COVID-19?

-

- COVID-19 is the short name for “coronavirus disease 2019.” It is a new virus. Doctors and scientists are still learning about it.

- Recently, this virus has made a lot of people sick. Scientists and doctors think that most people will be ok, especially kids, but some people might get pretty sick.

- Doctors and health experts are working hard to help people stay healthy.

What can I do so that I don’t get COVID-19?

-

- You can practice healthy habits at home, school, and play to help protect against the spread of COVID-19:

- Cough or sneeze into a tissue or your elbow. If you sneeze or cough into a tissue, throw it in the trash right away.

- Keep your hands out of your mouth, nose, and eyes. This will help keep germs out of your body.

- Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. Follow these five steps—wet, lather (make bubbles), scrub (rub together), rinse and dry. You can sing the “Happy Birthday” song twice.

- If you don’t have soap and water, have an adult help you use a special hand cleaner.

- Keep things clean. Older children can help adults at home and school clean the things we touch the most, like desks, doorknobs, light switches, and remote controls. (Note for adults: you can find more information about cleaning and disinfecting on CDC’s website.)

- If you feel sick, stay home. Just like you don’t want to get other people’s germs in your body, other people don’t want to get your germs either.

- You can practice healthy habits at home, school, and play to help protect against the spread of COVID-19:

What happens if you get sick with COVID-19?

-

- COVID-19 can look different in different people. For many people, being sick with COVID-19 would be a little bit like having the flu. People can get a fever, cough, or have a hard time taking deep breaths. Most people who have gotten COVID-19 have not gotten very sick. Only a small group of people who get it have had more serious problems. From what doctors have seen so far, most children don’t seem to get very sick. While a lot of adults get sick, most adults get better.

- If you do get sick, it doesn’t mean you have COVID-19. People can get sick from all kinds of germs. What’s important to remember is that if you do get sick, the adults at home and school will help get you any help that you need.

- If you suspect your child may have COVID-19, call the healthcare facility to let them know before you bring your child in to see them.

Information provided by https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/talking-with-children.html

CADCA Breakout Session: Over-the-Counter Medications

Over-The-Counter (OTC) Medicine Safety, Engaging Youth About Responsible Medicine Use

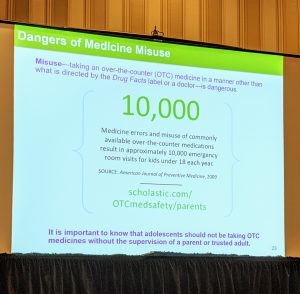

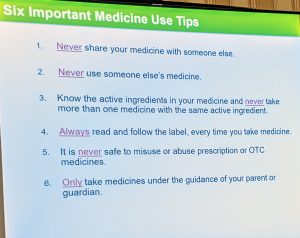

Through an information session we learned of an over-the-counter medication safety curriculum sponsored by Johnson & Johnson and Scholastic. The information shared here is essential when we work with community leaders, parents and guardians, in regards to the storage and securing of OTC in the home.

This curriculum can be delivered in small groups in as little as 45 minutes but can be expanded to include more information for a three hour session. There are promotional items, literature and engaging small group sessions designed to inform and educate  about issues related to unsecured OTC.

about issues related to unsecured OTC.

Over-The-Counter (OTC) medicines, when taken as directed are generally safe, but when taken incorrectly can cause significant harm. Research suggests that children begin to self-administer medication at age 11. Over 20,000 kids per year need medical attention due to medicine misuse.